Helen Grünwald ARCA (1925–1988)

Identifier

118.0000

Title

Helen Grünwald ARCA (1925–1988)

Type

person

Contributor

Jane Eckett

Birth Date

27 May 1925

Birthplace

Vienna, Austria

Death Date

21 June 1988

Place of death

St Mary's Hospital, Praed St, Westminster, London W2 1NY, England

Occupation

painter, muralist, printmaker, art teacher

Biography

Helen Mary Therese Grunwald was born in Vienna, as Helene Lillith Grunwald, and educated there at the Rudolf Steiner School. Her father, Robert Grunwald (1896–1951), was a concert violinist who reputedly worked with Bertolt Brecht, though would later give his occupation variously as teacher and writer, while her mother, Lillian Gladys Grunwald (1901–1982), ran a nursery school in Vienna and was later a kindergarten teacher in London (see ‘Naturalisation: Grunwald, Helene Lillith’, The London Gazette, no. 38541, 18 February 1949, p. 873; ‘Obituary: Lillian Gladys Grunwald’, ARJ Information, Association of Jewish Refugees in Great Britain, vol. XXXVII, no. 4, April 1982, p. 10).

In July 1939 Grunwald and her parents fled Vienna for Britain. Robert and Lillian Grunwald found temporary employment as wardens at ‘Loxleigh’—a hostel at Ilkley in West Yorkshire established by local Quakers and the Ilkley Committee of Jewish Refugees to accommodate teenaged boys arriving on the Kindertransport (see Caroline Brown, Ilkley at War, Cheltenham, UK: The History Press, 2006). Helen, then fourteen years of age, was billeted some twenty-seven kilometres away with a family by the name of Dickonson at 20 Kensington Terrace, Leeds (The National Archives, UK, 1939 Register, reference RG 101/3458A and RG 101/3670J). Her parents faced internment trials in October 1939 and, despite being initially exempted, were soon afterwards interned when the national policy towards ‘enemy aliens’ was tightened. Robert Grunwald was released from internment (location unknown) in September 1940 while his wife Lillian was released from the Isle of Man in February 1941 (The National Archives, UK, WW2 Internees (Aliens) Index Cards 1939–1947, reference HO 396/175). Lillian’s address prior to internment was given as 50 Northfield Road, N16, indicating the family had moved to Stoke Newington, in North London, by early 1940.

From 1941 to 1944 Helen Grunwald studied full-time at Beckenham School of Art, initially under official war artist Henry Carr RA RP RBA (1894–1970) before he was deployed to Algeria and Italy in 1942. Grunwald obtained her senior drawing certificate from the Kent Education Committee in May 1943 and proceeded to the Slade but did not continue owing to war conditions. Throughout the second half of the 1940s she continued to paint, whenever possible, from her parents’ lodgings at 11 Fairfax Road, NW6 (Swiss Cottage), exhibiting in group shows at the Leicester Galleries, Leger’s, the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA) and the Artists International Association (AIA).

From September 1945 to August 1948, she worked for a firm of religious art publishers—Pax House in Westminster—painting plaster saints. Despite her Jewish origins, Grunwald was, according to family friend Käthe Deutsch, ‘a passionate Christian, [and] an almost mystical believer’ (communication with the author, 2 June 2022). Certainly, Christian subjects were in evidence as early as 1946. When Grunwald’s Descent from the cross was exhibited, alongside the work of Mona Moore, a twenty-year-old Bryan Robertson—future curator of the Whitechapel Gallery—commended it as being ‘subdued in feeling and colour, full of thoughtful painting, well conceived and executed’ (Bryan Robertson, ‘The Younger British Artists’, The Studio, vol. 131, no. 636, March 1946, p. 75). The same painting was soon afterwards incorporated into a war memorial at St Andrew’s parish church in Croydon, where it was inscribed ‘A tribute to the fortitude of my people from 1940–1945’ (‘St. Andrew’s Memorial unveiled by Sir Ernest Cowell’, Croydon Times, London, 16 November 1946, p. 5). The work's present whereabouts are unknown (email from Lesley Carr, St Andrew's Church administrator, 17 June 2022).

Sir Kenneth Clark first saw her work at an AIA exhibition at Pall Mall, in 1945, and commented favourably. Clark’s comments were conveyed to Grunwald some three years later by Carel Weight CH CBE RA (1908–1997), in response to which Grunwald wrote to Clark on 10 May 1948—the first in a four decades’ long correspondence now preserved among Clark’s papers in the Tate Gallery Archives (TGA). Grunwald’s meticulously hand-written letters and Clark’s duplicate typescript replies reveal Clark’s willingness to assist a relatively unknown artist as he repeatedly provided letters of recommendation for Grunwald, assisting her whenever possible and occasionally purchasing her work. Indeed, on Clark’s first visit to Grunwald’s Fairfax Road studio, on 19 May 1948, he purchased her painting Victoria Station.

Grunwald held her first solo exhibition at William Ohly’s Berkeley Galleries, Mayfair, in July 1948. The modest exhibition comprised ten ‘atmospheric paintings of London’ (Our Time, vol. 7, no. 1 [or vol. 8, no. 14?], July 1948, p. 165) including Victoria Station, which Clark loaned for the occasion, and ‘quite a number of drawings’ (Grunwald to Clark, 27 June 1948, TGA 8812.1.2.2679). Ohly wrote to Clark, while the exhibition was on view, to ask his advice about Grunwald whom he believed was ‘very talented’, adding, ‘I should very much like to discuss with you what possibilities there would be to help this young lady, and to enable her to leave the factory work she is doing’ (Ohly to Clarke, 23 July 1948, TGA 8812/1/2/4847). This ‘factory work’ was the painting of plaster saints, which Grunwald found ‘uncongenial’, admitting to a loss of self-respect ‘working at this wretched job’ (Grunwald to Clark, 10 May 1948, and 27 June 1948, TGA, 8812.1.2.2675 and 2679). The exhibition was, in Grunwald’s view, ‘rather a success’, with the sale of ‘quite a number of paintings and drawings, which was a pleasant surprise’ (Grunwald to Clark, 1 August 1948, TGA, 8812.1.2.2681).

The exhibition at the Berkeley Galleries led to Grunwald moving soon afterwards to the Abbey Art Centre. A fortnight after the exhibition closed, Clark wrote to Grunwald: ‘Someone told me that you are working in Mr. Ohly’s monastery at Barnet, which I hope is true’ (Clark to Grunwald, 25 August 1948, TGA 8812.1.2.2682/1). The letter, however, was addressed to Fairfax Road, suggesting Grunwald may have initially only worked in a studio at the Abbey rather than taking up living quarters. By November 1948, when Grunwald applied for admission to the Royal College of Art (RCA), she gave her address for correspondence as that of the Abbey’s—89 Park Road, New Barnet, Herts (Helen Grunwald student file, registration forms, RCA, 26 November 1948). At the same time, Ohly again wrote to Clark that ‘Miss Grünewald [sic] is now at the Abbey & I hope she will be doing some good work’ (Ohly to Clark, 24 November 1948, TGA 8812/1/2/4848). The move, however, seems not to have been permanent for the following year she was back ‘in lodgings’ at 11 Fairfax Road (Helen Grunwald student file, registration forms, RCA, 29 September 1949), though in December 1949 she was listed among the Abbey’s residents in the electoral register (Electoral register record for 89 Park Road, Barnet East, London, 20 November 1949, London Metropolitan Archives). Alice Mary Fitzpayne, who first met Grunwald when sitting the RCA entrance exams, in February 1949, believes Grunwald only moved permanently to the Abbey after her father’s death in 1951 (correspondence from Alice Mary Fitzpayne, 22 March 2021). Nevertheless, Grunwald was evidently in residence in mid-1950, as was her newly arrived schoolfriend from Vienna, Angela Varga, when, at Grunwald’s invitation, Clark visited them both at the Abbey on 26 May 1950 (Clark to Ohly, 18 May 1950, TGA 8812/1/2/4850).

A love of baroque music attracted her to choirs and orchestras, which she regularly sketched in rehearsal. In August 1948 she attended the Three Choirs Festival in Worcester, where, in addition to sketching during performances of the London Philharmonic Orchestra, she drew portraits of such renowned composers and musicians as Sir Ivor Atkins (1869–1953), Zoltan Kádaly (1882–1967), Sir George Dyson (1883–1964) and Edmund Rubbra (1901–1986) as well as painting a portrait of contralto Kathleen Ferrier CBE (1912–1953), who gave her two sittings (Grunwald to Clark, 18 September 1948, TGA 8812/1/2/2684).

Grunwald held a second exhibition at the Berkeley Galleries in May 1949. This time she showed thirty-five paintings, all made at the Abbey over the previous six months (Grunwald to Clarke, 16 May 1949, TGA 8812/1/2/2687) and described on the invitation as ‘Impressions and paintings of London: The churches, markets, life of the city’. In addition to her work, visitors to the gallery that month could also see that of Swiss dramatist, painter, and illustrator Georgette Boner (1903–1998), who exhibited her illustrations to the Chinese classic, Monkey (which she also transcribed into German), sculptor Arthur Mackenzie (who later changed his name to George Kennethson, 1910–1994), and drawings by German émigré Milein Cosman (who had attended the same Swiss school as Ohly’s son Ernest during the war). The combined invitation to all four shows billed Grunwald and Cosman as ‘Two Young Artists of Promise’ being ‘presented’ by the Abbey Art Centre (despite Cosman not being an Abbey resident). A quote from one of Clark’s references for Grunwald was used on the invitation: ‘Thoughtful and independent. A remarkable combination of the poetical and the concrete’ (see Invitation to four exhibitions at the Berkeley Galleries, London: Georgette Boner, Milein Cosman, Helen Grunwald, and Arthur Mackenzie, opening 6 May 1949). The exhibition was a success, with Clark purchasing from it several more works of Grunwald’s and Eric Newton personally congratulating her (as conveyed by Grunwald to Clark, 24 May 1949, TGA 8812/1/2/2688/2).

In July 1949 Ohly included Grunwald in a group exhibition at the Berkley Galleries, this time alongside several Abbey residents: James Gleeson, Peter Graham, Grahame King, Robert Klippel, Max Newton, Mary Webb, and Inge Winter (who would become Inge King the following year); see ‘Exhibition of small paintings & sculpture during July, Berkeley Galleries, 20 Davies St, London, July [1949]’). In addition to these Australian expatriates from the Abbey, the exhibition included the usual eclectic array of cosmopolitan émigré and refugee artists such as Karin Jonzen, Uli Nimptsch, Anthony Levett Prinsep, and Fred Uhlman, as well as Belfast-man Gerard Dillon, and sculptor Henry Moore, whose work effectively underwrote the risk of showing lesser-known artists from central Europe and the former British dominions.

Grunwald sat the three-day entrance exams for admission to the RCA in February 1949 and commenced the Diploma course in September 1949, with the hope that the course would qualify her to teach art therapy. Over the preceding summer she doubted the financial feasibility of studying, writing to Clark she might need to stop painting and instead take up work with the Land Army (‘I prefer cows to chimney pots + smoke’), but a special scholarship from the College was arranged, putting an end to this drastic move (Grunwald to Clark, 24 May 1949, TGA 8812/1/2/2688/2). Clark also supported her applications to various local authorities for financial assistance; one reference from him described Grunwald as an artist of ‘exceptional promise’ who had surmounted ‘a number of very serious difficulties in order to keep on with her painting’, showing herself to be ‘conscientious, determined and independent’, and noting that while her painting was occasionally uneven, with ‘wooliness of handling’, this was compensated for by ‘real quality and imagination’ (Clark, reference for Grunwald, 17 October 1949, TGA 8812/1/2/2692). Carel Weight, who had first encouraged Grunwald to apply, in late-1948, oversaw her three-year course of studies. Comments (presumably Weight’s) on her student record include: ‘produces interesting work on a very small scale’ and ‘interesting personal work’ (RCA, Progress reports during college course, Special Collections, RCA, 1950/51 and 1951/52).

Grunwald confided in Alice Mary Fitzpayne, whom she first met at the RCA, ‘that she felt sure she was to be as fine an artist as Rembrandt, or, if that was not the case, she would have 20 children!’ For her part, Fitzpayne acknowledged Grunwald’s ‘tremendous artistic gifts’ while also recalling an occasion when Sir Kenneth Clark was about to give a talk to the RCA students and Grunwald ‘appeared in front of him with a board she had prepared for him, the paint glistening with oily wetness, he attempting to receive the present without getting his hands and clothes covered in oil paint’ (Alice Mary Fitzpayne, London, written responses, March 2021). She also recalled Grunwald had always ‘yearned for an artistic circle’ and ‘the Abbey Art Centre certainly fulfilled this need’.

Grunwald was joined at the Abbey in early 1950 by her Viennese schoolfriend: fellow artist Angela Varga (whose sister Kate Varga was then working in England as a nurse; Kate would later marry Abbey sculptor Peter King, whom she met at the Abbey). In March that year, Clark’s secretary gave Grunwald and Varga a private tour of his collection, Clark being away at the time. Writing to thank him for the privilege, Grunwald invited Clark to the Abbey: ‘I don’t think you have ever been to the Art Centre, and I don’t think it would be wasting your time if you could manage to come and see everything out here. The place itself is quite fascinating, so it would not merely mean bothering you on account of my work. The Abbey is not a very great distance from Hampstead [where Clark lived, at Upper Terrace House], so I hope I am not suggesting something impossible. Incidentally, there are other “Artists at work” here, whose work might interest you, so I am very much hoping you would care to come’ (Grunwald to Clark, 24 May 1949, TGA 8812/1/2/2693). A second letter followed, asking him specifically to view the work of Angela Varga, who ‘only narrowly escaped being transported by the Nazis during the war’; Varga was due to return to Vienna in June, and Grunwald hoped Clark might write a reference for her to support her return to England to study at ‘one of the London Schools of Art, or possibly, the Slade’ (Grunwald to Clark, 24 May 1949, TGA 8812/1/2/2696). Clark accepted Grunwald’s invitation, writing in advance to Ohly that ‘Miss Grunwald is very anxious for me to see the work of a girl named Angela Varga, who is a student at the Abbey’ and proposing a mutually convenient date (Clark to Ohly, 18 May 1950, TGA 8812/1/2/4850). The visit eventuated in the late afternoon of 26 May 1950. Ohly introduced Clark to the Abbey’s residents, including Alan Davie (whose jewellery Clark saw, and was impressed with, but whose paintings he had not time to see), and new arrivals Bernard Smith and Kate Smith, later apologising ‘for introducing so many people but they would have been so disappointed’ (Ohly to Clark, 6 June 1950, TGA 8812/1/2/4852, and Davie to Clark, 10 January 1951, TGA 8812/1/2/1730). Clark soon afterwards provided the much-needed reference for ‘Miss Weiss-Varga’, commenting to Grunwald that ‘it must be lovely for you to find someone with a talent so akin to your own, because, although there are naturally differences in your work, the vision and sympathies are very much the same’ (Clark to Grunwald, 30 May 1950, TGA 8812/1/2/2698). A week later, Varga was accepted at the Slade (Grunwald to Clark, 7 June 1949, TGA 8812/1/2/2699) and by mid-October had returned to the Abbey to embark on her studies at the Slade.

Grunwald holidayed in France in the summer of 1950, writing afterwards to Clark: ‘I have been to France and since then my colour has lightened, and I hope there is an improvement generally. I may exhibit a number of works in December’ (Grunwald to Clark, 16 October 1950, TGA 8812/1/2/2700). Clark was in Italy for much of 1951, but on his return to London at the end of the year invited Grunwald and Varga to bring ‘some specimens’ of their recent work to his home in Hampstead (Clark to Grunwald, 17 December 1951, TGA 8812/1/2/2705). As a result of the visit, Clark purchased two small works of Varga’s: 'Paris Meat Market [which] was marked 12 gns at the Exhibition’ and The Fish, which were not priced at all but for Grunwald suggested 4 or 5 guineas given its small size (Grunwald to Clark, 5 January 1951 [sic, should be 1952], TGA 8812/1/2/2707, and Clark to Grunwald, 16 January 1952, TGA 8812/1/2/2708).

Grunwald’s father Robert died in October 1951. At the time of Robert’s death, Grunwald’s parents were living a short walk south of the Abbey Art Centre at 18 Bohun Road, East Barnet. Grunwald’s mother Lillian now joined Helen at the Abbey. Whether Lillian continued teaching at the Hampstead Garden Suburb Jewish Kindergarten (attached to the synagogue in Norrice Lea, Lyttlelton Road, N2), which she had assisted Miriam Bornstein in establishing in 1949, is unknown (‘Hampstead Garden Synagogue. Jewish Kindergarten Opened’, The Jewish Chronicle, London, 20 May 1949, p. 20; ‘Naturalisation: Lillian Gladys Grunwald', The London Gazette, no. 40232, 16 July 1954, p. 4166, both articles courtesy Ben Uri Research Unit / BURU). However, by May 1952 Grunwald confided in Clark that her mother was in ‘a mental home’, suffering from a nervous breakdown, adding that the experience of looking after her mother during the upheavals of her mother’s ‘frequent illness’ had led Grunwald to consider a career in art therapy (Grunwald to Clark, 19 May 1952 and 23 June 1952, TGA 8812/1/2/2708/1 and 8812/1/2/2709).

In the lead-up to her RCA Diploma Exhibition, 9–15 June 1952, Grunwald warned Clark that ‘it is rather a “restrained” output, for although I feel I have learned a great deal [about] drawing and constructive thinking, I have not been influenced by “modern” trends of thought or technique’ (Grunwald to Clark, 19 May 1952, TGA 8812/1/2/2708/1). She graduated ARCA Diploma in Painting in 1952 with a disappointing ‘Pass’ (the grading of Diplomas as first, second and pass being then a recent development). Grunwald again wrote to Clark: chagrined that her work should have been hung in college exhibitions and even awarded (with two other students) a drawing prize, yet the ‘the spirit of my work was not altogether pleasing to some of the people concerned in this matter’. She reported that Carel Weight tried to intercede on her behalf but had advised her it was ‘not sufficiently colourful and “modern”’ (Grunwald to Clark, 23 June 1952, TGA 8812/1/2/2709). Clark responded sympathetically and pragmatically: writing he was ‘more than ever shocked that you did not receive a higher diploma’, purchasing another of her works for £25, and offering advice re the massing of light and dark areas in a way that the subject can be easily grasped—suggesting she look to Sickert in this regard (Clark to Grunwald, 10 July 1952, TGA 8812/1/2/2710).

Grunwald spent that summer working at a National Union of Students (NUS) camp at Catfield, Norfolk, picking fruit and sketching landscapes in her spare time, afterwards painting landscapes at Essex and Suffolk (Grunwald to Clark, 17 July 1952 and 22 August 1952, TGA 8812/1/2/2711 and 8812/1/2/2713).

She commenced teaching in February 1953, initially at a private school—possibly Ashby Secondary Modern Girls’ School at Scunthorpe, Lincolnshire, for which Clark agreed to supply a written reference while hoping she would secure a more sympathetic post (Clark to Grunwald, 17 December 1952, TGA 8812/1/2/2717). After six months she moved, in September 1953, to Fort Pitt Technical School at Chatham in Kent, where she found the art department facilities to be excellent though she struggled to find sufficient time to paint (Grunwald to Clark, 22 November 1953, TGA 8812/1/2/2718). During the 1960s and 1970s Grunwald taught art at Paddington and Maida Vale High School (originally an all-girls school, it amalgamated with North Paddington School in 1972 to become the mixed-sex Paddington School; see T F T Baker, Diane K Bolton and Patricia E C Croot, ‘Paddington: Education’, in A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 9, Hampstead, Paddington, ed. C R Elrington (London, 1989), pp. 265-271. British History Online). There her students included the future Turner Prize winner Lubaina Himid (information from Louise Shalev née Gordon via Monica Bohm-Duchen, 11 May 2022). Among the many student exhibitions that she organised for the school was People to People, ‘which set out to create mutual understanding and interest among different peoples’ (‘People to People Art’, Marylebone Mercury, London, 1 December 1967, p. 4). While she later referred to this aspect of her work as ‘the dreaded teaching’, she appreciated its ‘beneficial side — simplifying ideas, formulating and observing things which one had perhaps neglected as a student’ (Grunwald to Clark, 11 October 1976, TGA 8812/1/3/1235/1). She remained as art mistress at Paddington School until the late 1970s.

In addition to teaching, Grunwald also painted murals. An extension to St Thomas of Canterbury Church in Canterbury, Kent, in 1963, saw the construction of a new chapel on the north side of the church, for which Grunwald received her first major commission. The Canterbury Saints depicts Christ surrounded by a dozen saints, including St Augustine of Canterbury (founder of the Christian church in southern England) and Pope Gregory, as well as nuns and monks, all set within a trompe l’oeil architectural structure. Grunwald later glimpsed her mural on television, which prompted her to think further about ‘the three fold unity of the sound, structure of building + drawing’ and resulted in a new series of work that she exhibited in 1975 (Grunwald to Clark, 10 March 1975, TGA 8812/1/3/1234). She also painted murals for the Americana club in Croydon, London, c. 1975 (as mentioned briefly in The Stage and Television Today, 18 September 1975, p. 6).

Helen and Lillian Grunwald eventually left the Abbey in the mid-1970s, moving to a flat at 48 Blomfield Road, Little Venice, where they remained for the rest of their lives (their presence at the Abbey as late as 1965 is documented in the London Metropolitan Archives, Electoral Registers, Barnet, England, LCC/PER/B/2986). They continued to live together until Lillian’s death in 1982. Mother and daughter shared many of the same interests, both becoming adherents of the esoteric philosophy group centred about George Gurdjieff (who died in Paris in 1949) and his London followers, particularly the group centred around the Jungian psychoanalyst Maurice Nicholl (1884–1953). Another friend of Grunwald's and Fitzpayne's, also associated with the Nicholl group, was Dorothy King who headed the South London Art Gallery. Mary Alice Fitzpayne sketched Helen and Lillian performing what she referred to as ‘Grecian’ dancing, in long robes, to the sounds of an accompanying gramaphone; the sketches remain in Fitzpayne’s possession. The dancing was likely inspired by Gurdjieff's 'sacred movements' or Rudolf Steiner's 'Eurythy', which is taught at Waldorf schools worldwide.

Lillian died in January 1982; Helen would survive her by only six years (General Register Office, UK, vol. 15, pp. 1479, 2323).

Grunwald’s love of music—particularly Bach—drew her to the Tilford Choir and Orchestra, which she regularly sketched throughout the 1960s and ‘70s. In June 1975 she exhibited these pen and ink sketches along with large, abstracted paintings in the porch and baptistry of St George’s Church, Hanover Square, W1, coinciding with the Tilford Bach Festival Choir and Orchestra’s third annual week of Bach in London (Janet Watts, ‘Colouring Bach’, The Guardian, 25 June 1975, p. 11, article courtesy BURU). She also executed a number of what she termed ‘decorations’ for the Tilford Bach Choir, which were used, for instance, for their 1976–77 season program. Clark thought them ‘beautifully drawn, but … You are best at drawings of living people, like the Orchestra, and the Tilford Bach Choir, and they do not gain by being made into decorations’, suggesting again she consider going into book illustration (Clark to Grunwald, 14 October 1976, TGA, 8812.1.3.1236). She again exhibited at St George’s, Hanover Square, for the third London Handel Festival (27 April to 4 May 1980). In the month before the exhibition, Sir Ernst Grombrich visited Grunwald at her Blomfield Road studio to inspect the work—about which he had agreed to write for the festival program. Grunwald reported Gombrich’s visit to Clark: ‘Sir Ernst says Ruskin would have liked my work—& that I could do stained glass design’ (Grunwald to Clark, 27 March 1980, TGA, 8812.1.3.1237). In May 1985 she exhibited new paintings and drawings under the title ‘Bach in Splendour’ at St Anne and St Agnes on Gresham Street in the city of London (The Times, London, 16 April 1985, p. 36).

The canal-side scenes and streets of old houses around Little Venice became an increasing focus for her work in the 1970s and she became well-known in local artistic circles, even initiating ‘an experimental “group” about once every four weeks, when a few artists and musicians meet, to paint, or write together, or make music, or even just relax!’ (Grunwald to Fitzpayne, 8 October 1976, private collection). She also experimented with lithography and linocut printmaking at this time. In 1978 the Marylebone Local History Room acquired forty-two of drawings and lithographs of north Westminster scenes and exhibited them at Marylebone Library (Westminister City Libraries, Annual Report of the City Librarian, 1978-79, p. 7). In November 1980 she held a second exhibition of drawings of Marylebone, Mayfair and Paddington at Marylebone Library. Studies of old houses—including Handel’s home in Brock Street—were interspersed with market studies (Noreen Caffrey, ‘Historic scenes captured in local exhibition’, Marylebone Mercury, London, 28 November 1980, p. 11, illustrated). An exhibition in the visitor’s gallery of the Stock Exchange, in 1984, was titled Helen Mary Grunwald: the changing, changeless city; drawings, paintings, prints, indicating her preoccupations with her physical environs. A vignette drawing of the Saint Mary Magdalene Church, with canal boats moored in the foreground, near to her home in Blomfield Road, would constitute her personal letterhead in the 1980s.

Her final major commission, received in 1985 and part-funded by Westminster Council, was to paint a series of Byzantine-style murals for the apse of a 130-year-old Russian Chapel at 32 Welbeck Street, Marylebone (‘A Russian Chapel in Marylebone’, Ecclesiological Society Newsletter, no. 16, April 1985, p. 11). The chapel had been unused for many years and the building’s then tenants, the Variety Club of Great Britain, who had applied without success to alter the building, accepted the council’s offer to meet half the cost of restoring the chapel. Grunwald’s commission formed part of the restoration process. Local newspapers compared Grunwald to Michelangelo, as she worked on scaffolding for six months to complete the work. ‘The main theme of the murals’, she initially told a reporter, ‘is healing the sick because Variety Club do a lot of charitable work in this field especially with children’ (Graham James, ‘Restored to glory’, Paddington Mercury, London, 24 January 1986, p. 24, illustrated). However, the Association of Jewish Refugees in Britain later reported that Grunwald chose the theme of human suffering and resurrection, with many parallels to Nazi persecution and racial intolerance, and a depiction of the gas chambers (C.A. ‘Helen Grunwald's Murals’, ARJ Information, vol. XLI, no. 12, Dec 1986, p. 6). When unveiled in mid-1986, the Variety Club reportedly ‘reacted in horror’, claiming Grunwald ‘had got carried away with her own enthusiasm’ and that the religious atmosphere was not ‘conducive to work’ (‘‘Niet, niet’, to work of art’, Marylebone Mercury, London, 14 August 1986, p. 1). Despite the work being praised by Canon David, Bishop of Norwich Cathedral and chairman of Art in Churches, the tenants erected screens to block the view of the murals, which were eventually painted over (Barlett School of Architecture, University College London, Survey of London: vols. 51 and 52, South-East Marylebone, London: UCL, 2017, chapter 14, p. 23 of draft version, check page ref for printed publication).

Helen Grunwald died of a cerebral infarction and vasultis, 21 June 1988, aged 63, at St Mary's Hospital, Westminster (General Register Office, UK, 1988, vol. 15, p. 1479, and Death certificate, registered City of Wesminster, 14 June 1988, application no. 12179018/1, QBDAC 347492). She was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery.

Her will requested she be buried according to the rites of the Church of England, but with the service shared with a Catholic priest, a Buddhist, and a Rabbi. While she left no next-of-kin, she made generous provision for the care of her cat and left her flat to a friend, Miss Marjorie Wardle. The remainder of her estate was split between various named charities and her artworks sold. The final paragraph of her will read: "May religion cease to be a cause of division and may our trickle of endeavour and love penetrate the chemical waste land of inner and outer destruction and desolation" (information kindly supplied by Catherine Hill, The National Archives, Kew, 24 April 2023).

Jane Eckett

31 May 2022

(updated 25 April 2023)

In July 1939 Grunwald and her parents fled Vienna for Britain. Robert and Lillian Grunwald found temporary employment as wardens at ‘Loxleigh’—a hostel at Ilkley in West Yorkshire established by local Quakers and the Ilkley Committee of Jewish Refugees to accommodate teenaged boys arriving on the Kindertransport (see Caroline Brown, Ilkley at War, Cheltenham, UK: The History Press, 2006). Helen, then fourteen years of age, was billeted some twenty-seven kilometres away with a family by the name of Dickonson at 20 Kensington Terrace, Leeds (The National Archives, UK, 1939 Register, reference RG 101/3458A and RG 101/3670J). Her parents faced internment trials in October 1939 and, despite being initially exempted, were soon afterwards interned when the national policy towards ‘enemy aliens’ was tightened. Robert Grunwald was released from internment (location unknown) in September 1940 while his wife Lillian was released from the Isle of Man in February 1941 (The National Archives, UK, WW2 Internees (Aliens) Index Cards 1939–1947, reference HO 396/175). Lillian’s address prior to internment was given as 50 Northfield Road, N16, indicating the family had moved to Stoke Newington, in North London, by early 1940.

From 1941 to 1944 Helen Grunwald studied full-time at Beckenham School of Art, initially under official war artist Henry Carr RA RP RBA (1894–1970) before he was deployed to Algeria and Italy in 1942. Grunwald obtained her senior drawing certificate from the Kent Education Committee in May 1943 and proceeded to the Slade but did not continue owing to war conditions. Throughout the second half of the 1940s she continued to paint, whenever possible, from her parents’ lodgings at 11 Fairfax Road, NW6 (Swiss Cottage), exhibiting in group shows at the Leicester Galleries, Leger’s, the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA) and the Artists International Association (AIA).

From September 1945 to August 1948, she worked for a firm of religious art publishers—Pax House in Westminster—painting plaster saints. Despite her Jewish origins, Grunwald was, according to family friend Käthe Deutsch, ‘a passionate Christian, [and] an almost mystical believer’ (communication with the author, 2 June 2022). Certainly, Christian subjects were in evidence as early as 1946. When Grunwald’s Descent from the cross was exhibited, alongside the work of Mona Moore, a twenty-year-old Bryan Robertson—future curator of the Whitechapel Gallery—commended it as being ‘subdued in feeling and colour, full of thoughtful painting, well conceived and executed’ (Bryan Robertson, ‘The Younger British Artists’, The Studio, vol. 131, no. 636, March 1946, p. 75). The same painting was soon afterwards incorporated into a war memorial at St Andrew’s parish church in Croydon, where it was inscribed ‘A tribute to the fortitude of my people from 1940–1945’ (‘St. Andrew’s Memorial unveiled by Sir Ernest Cowell’, Croydon Times, London, 16 November 1946, p. 5). The work's present whereabouts are unknown (email from Lesley Carr, St Andrew's Church administrator, 17 June 2022).

Sir Kenneth Clark first saw her work at an AIA exhibition at Pall Mall, in 1945, and commented favourably. Clark’s comments were conveyed to Grunwald some three years later by Carel Weight CH CBE RA (1908–1997), in response to which Grunwald wrote to Clark on 10 May 1948—the first in a four decades’ long correspondence now preserved among Clark’s papers in the Tate Gallery Archives (TGA). Grunwald’s meticulously hand-written letters and Clark’s duplicate typescript replies reveal Clark’s willingness to assist a relatively unknown artist as he repeatedly provided letters of recommendation for Grunwald, assisting her whenever possible and occasionally purchasing her work. Indeed, on Clark’s first visit to Grunwald’s Fairfax Road studio, on 19 May 1948, he purchased her painting Victoria Station.

Grunwald held her first solo exhibition at William Ohly’s Berkeley Galleries, Mayfair, in July 1948. The modest exhibition comprised ten ‘atmospheric paintings of London’ (Our Time, vol. 7, no. 1 [or vol. 8, no. 14?], July 1948, p. 165) including Victoria Station, which Clark loaned for the occasion, and ‘quite a number of drawings’ (Grunwald to Clark, 27 June 1948, TGA 8812.1.2.2679). Ohly wrote to Clark, while the exhibition was on view, to ask his advice about Grunwald whom he believed was ‘very talented’, adding, ‘I should very much like to discuss with you what possibilities there would be to help this young lady, and to enable her to leave the factory work she is doing’ (Ohly to Clarke, 23 July 1948, TGA 8812/1/2/4847). This ‘factory work’ was the painting of plaster saints, which Grunwald found ‘uncongenial’, admitting to a loss of self-respect ‘working at this wretched job’ (Grunwald to Clark, 10 May 1948, and 27 June 1948, TGA, 8812.1.2.2675 and 2679). The exhibition was, in Grunwald’s view, ‘rather a success’, with the sale of ‘quite a number of paintings and drawings, which was a pleasant surprise’ (Grunwald to Clark, 1 August 1948, TGA, 8812.1.2.2681).

The exhibition at the Berkeley Galleries led to Grunwald moving soon afterwards to the Abbey Art Centre. A fortnight after the exhibition closed, Clark wrote to Grunwald: ‘Someone told me that you are working in Mr. Ohly’s monastery at Barnet, which I hope is true’ (Clark to Grunwald, 25 August 1948, TGA 8812.1.2.2682/1). The letter, however, was addressed to Fairfax Road, suggesting Grunwald may have initially only worked in a studio at the Abbey rather than taking up living quarters. By November 1948, when Grunwald applied for admission to the Royal College of Art (RCA), she gave her address for correspondence as that of the Abbey’s—89 Park Road, New Barnet, Herts (Helen Grunwald student file, registration forms, RCA, 26 November 1948). At the same time, Ohly again wrote to Clark that ‘Miss Grünewald [sic] is now at the Abbey & I hope she will be doing some good work’ (Ohly to Clark, 24 November 1948, TGA 8812/1/2/4848). The move, however, seems not to have been permanent for the following year she was back ‘in lodgings’ at 11 Fairfax Road (Helen Grunwald student file, registration forms, RCA, 29 September 1949), though in December 1949 she was listed among the Abbey’s residents in the electoral register (Electoral register record for 89 Park Road, Barnet East, London, 20 November 1949, London Metropolitan Archives). Alice Mary Fitzpayne, who first met Grunwald when sitting the RCA entrance exams, in February 1949, believes Grunwald only moved permanently to the Abbey after her father’s death in 1951 (correspondence from Alice Mary Fitzpayne, 22 March 2021). Nevertheless, Grunwald was evidently in residence in mid-1950, as was her newly arrived schoolfriend from Vienna, Angela Varga, when, at Grunwald’s invitation, Clark visited them both at the Abbey on 26 May 1950 (Clark to Ohly, 18 May 1950, TGA 8812/1/2/4850).

A love of baroque music attracted her to choirs and orchestras, which she regularly sketched in rehearsal. In August 1948 she attended the Three Choirs Festival in Worcester, where, in addition to sketching during performances of the London Philharmonic Orchestra, she drew portraits of such renowned composers and musicians as Sir Ivor Atkins (1869–1953), Zoltan Kádaly (1882–1967), Sir George Dyson (1883–1964) and Edmund Rubbra (1901–1986) as well as painting a portrait of contralto Kathleen Ferrier CBE (1912–1953), who gave her two sittings (Grunwald to Clark, 18 September 1948, TGA 8812/1/2/2684).

Grunwald held a second exhibition at the Berkeley Galleries in May 1949. This time she showed thirty-five paintings, all made at the Abbey over the previous six months (Grunwald to Clarke, 16 May 1949, TGA 8812/1/2/2687) and described on the invitation as ‘Impressions and paintings of London: The churches, markets, life of the city’. In addition to her work, visitors to the gallery that month could also see that of Swiss dramatist, painter, and illustrator Georgette Boner (1903–1998), who exhibited her illustrations to the Chinese classic, Monkey (which she also transcribed into German), sculptor Arthur Mackenzie (who later changed his name to George Kennethson, 1910–1994), and drawings by German émigré Milein Cosman (who had attended the same Swiss school as Ohly’s son Ernest during the war). The combined invitation to all four shows billed Grunwald and Cosman as ‘Two Young Artists of Promise’ being ‘presented’ by the Abbey Art Centre (despite Cosman not being an Abbey resident). A quote from one of Clark’s references for Grunwald was used on the invitation: ‘Thoughtful and independent. A remarkable combination of the poetical and the concrete’ (see Invitation to four exhibitions at the Berkeley Galleries, London: Georgette Boner, Milein Cosman, Helen Grunwald, and Arthur Mackenzie, opening 6 May 1949). The exhibition was a success, with Clark purchasing from it several more works of Grunwald’s and Eric Newton personally congratulating her (as conveyed by Grunwald to Clark, 24 May 1949, TGA 8812/1/2/2688/2).

In July 1949 Ohly included Grunwald in a group exhibition at the Berkley Galleries, this time alongside several Abbey residents: James Gleeson, Peter Graham, Grahame King, Robert Klippel, Max Newton, Mary Webb, and Inge Winter (who would become Inge King the following year); see ‘Exhibition of small paintings & sculpture during July, Berkeley Galleries, 20 Davies St, London, July [1949]’). In addition to these Australian expatriates from the Abbey, the exhibition included the usual eclectic array of cosmopolitan émigré and refugee artists such as Karin Jonzen, Uli Nimptsch, Anthony Levett Prinsep, and Fred Uhlman, as well as Belfast-man Gerard Dillon, and sculptor Henry Moore, whose work effectively underwrote the risk of showing lesser-known artists from central Europe and the former British dominions.

Grunwald sat the three-day entrance exams for admission to the RCA in February 1949 and commenced the Diploma course in September 1949, with the hope that the course would qualify her to teach art therapy. Over the preceding summer she doubted the financial feasibility of studying, writing to Clark she might need to stop painting and instead take up work with the Land Army (‘I prefer cows to chimney pots + smoke’), but a special scholarship from the College was arranged, putting an end to this drastic move (Grunwald to Clark, 24 May 1949, TGA 8812/1/2/2688/2). Clark also supported her applications to various local authorities for financial assistance; one reference from him described Grunwald as an artist of ‘exceptional promise’ who had surmounted ‘a number of very serious difficulties in order to keep on with her painting’, showing herself to be ‘conscientious, determined and independent’, and noting that while her painting was occasionally uneven, with ‘wooliness of handling’, this was compensated for by ‘real quality and imagination’ (Clark, reference for Grunwald, 17 October 1949, TGA 8812/1/2/2692). Carel Weight, who had first encouraged Grunwald to apply, in late-1948, oversaw her three-year course of studies. Comments (presumably Weight’s) on her student record include: ‘produces interesting work on a very small scale’ and ‘interesting personal work’ (RCA, Progress reports during college course, Special Collections, RCA, 1950/51 and 1951/52).

Grunwald confided in Alice Mary Fitzpayne, whom she first met at the RCA, ‘that she felt sure she was to be as fine an artist as Rembrandt, or, if that was not the case, she would have 20 children!’ For her part, Fitzpayne acknowledged Grunwald’s ‘tremendous artistic gifts’ while also recalling an occasion when Sir Kenneth Clark was about to give a talk to the RCA students and Grunwald ‘appeared in front of him with a board she had prepared for him, the paint glistening with oily wetness, he attempting to receive the present without getting his hands and clothes covered in oil paint’ (Alice Mary Fitzpayne, London, written responses, March 2021). She also recalled Grunwald had always ‘yearned for an artistic circle’ and ‘the Abbey Art Centre certainly fulfilled this need’.

Grunwald was joined at the Abbey in early 1950 by her Viennese schoolfriend: fellow artist Angela Varga (whose sister Kate Varga was then working in England as a nurse; Kate would later marry Abbey sculptor Peter King, whom she met at the Abbey). In March that year, Clark’s secretary gave Grunwald and Varga a private tour of his collection, Clark being away at the time. Writing to thank him for the privilege, Grunwald invited Clark to the Abbey: ‘I don’t think you have ever been to the Art Centre, and I don’t think it would be wasting your time if you could manage to come and see everything out here. The place itself is quite fascinating, so it would not merely mean bothering you on account of my work. The Abbey is not a very great distance from Hampstead [where Clark lived, at Upper Terrace House], so I hope I am not suggesting something impossible. Incidentally, there are other “Artists at work” here, whose work might interest you, so I am very much hoping you would care to come’ (Grunwald to Clark, 24 May 1949, TGA 8812/1/2/2693). A second letter followed, asking him specifically to view the work of Angela Varga, who ‘only narrowly escaped being transported by the Nazis during the war’; Varga was due to return to Vienna in June, and Grunwald hoped Clark might write a reference for her to support her return to England to study at ‘one of the London Schools of Art, or possibly, the Slade’ (Grunwald to Clark, 24 May 1949, TGA 8812/1/2/2696). Clark accepted Grunwald’s invitation, writing in advance to Ohly that ‘Miss Grunwald is very anxious for me to see the work of a girl named Angela Varga, who is a student at the Abbey’ and proposing a mutually convenient date (Clark to Ohly, 18 May 1950, TGA 8812/1/2/4850). The visit eventuated in the late afternoon of 26 May 1950. Ohly introduced Clark to the Abbey’s residents, including Alan Davie (whose jewellery Clark saw, and was impressed with, but whose paintings he had not time to see), and new arrivals Bernard Smith and Kate Smith, later apologising ‘for introducing so many people but they would have been so disappointed’ (Ohly to Clark, 6 June 1950, TGA 8812/1/2/4852, and Davie to Clark, 10 January 1951, TGA 8812/1/2/1730). Clark soon afterwards provided the much-needed reference for ‘Miss Weiss-Varga’, commenting to Grunwald that ‘it must be lovely for you to find someone with a talent so akin to your own, because, although there are naturally differences in your work, the vision and sympathies are very much the same’ (Clark to Grunwald, 30 May 1950, TGA 8812/1/2/2698). A week later, Varga was accepted at the Slade (Grunwald to Clark, 7 June 1949, TGA 8812/1/2/2699) and by mid-October had returned to the Abbey to embark on her studies at the Slade.

Grunwald holidayed in France in the summer of 1950, writing afterwards to Clark: ‘I have been to France and since then my colour has lightened, and I hope there is an improvement generally. I may exhibit a number of works in December’ (Grunwald to Clark, 16 October 1950, TGA 8812/1/2/2700). Clark was in Italy for much of 1951, but on his return to London at the end of the year invited Grunwald and Varga to bring ‘some specimens’ of their recent work to his home in Hampstead (Clark to Grunwald, 17 December 1951, TGA 8812/1/2/2705). As a result of the visit, Clark purchased two small works of Varga’s: 'Paris Meat Market [which] was marked 12 gns at the Exhibition’ and The Fish, which were not priced at all but for Grunwald suggested 4 or 5 guineas given its small size (Grunwald to Clark, 5 January 1951 [sic, should be 1952], TGA 8812/1/2/2707, and Clark to Grunwald, 16 January 1952, TGA 8812/1/2/2708).

Grunwald’s father Robert died in October 1951. At the time of Robert’s death, Grunwald’s parents were living a short walk south of the Abbey Art Centre at 18 Bohun Road, East Barnet. Grunwald’s mother Lillian now joined Helen at the Abbey. Whether Lillian continued teaching at the Hampstead Garden Suburb Jewish Kindergarten (attached to the synagogue in Norrice Lea, Lyttlelton Road, N2), which she had assisted Miriam Bornstein in establishing in 1949, is unknown (‘Hampstead Garden Synagogue. Jewish Kindergarten Opened’, The Jewish Chronicle, London, 20 May 1949, p. 20; ‘Naturalisation: Lillian Gladys Grunwald', The London Gazette, no. 40232, 16 July 1954, p. 4166, both articles courtesy Ben Uri Research Unit / BURU). However, by May 1952 Grunwald confided in Clark that her mother was in ‘a mental home’, suffering from a nervous breakdown, adding that the experience of looking after her mother during the upheavals of her mother’s ‘frequent illness’ had led Grunwald to consider a career in art therapy (Grunwald to Clark, 19 May 1952 and 23 June 1952, TGA 8812/1/2/2708/1 and 8812/1/2/2709).

In the lead-up to her RCA Diploma Exhibition, 9–15 June 1952, Grunwald warned Clark that ‘it is rather a “restrained” output, for although I feel I have learned a great deal [about] drawing and constructive thinking, I have not been influenced by “modern” trends of thought or technique’ (Grunwald to Clark, 19 May 1952, TGA 8812/1/2/2708/1). She graduated ARCA Diploma in Painting in 1952 with a disappointing ‘Pass’ (the grading of Diplomas as first, second and pass being then a recent development). Grunwald again wrote to Clark: chagrined that her work should have been hung in college exhibitions and even awarded (with two other students) a drawing prize, yet the ‘the spirit of my work was not altogether pleasing to some of the people concerned in this matter’. She reported that Carel Weight tried to intercede on her behalf but had advised her it was ‘not sufficiently colourful and “modern”’ (Grunwald to Clark, 23 June 1952, TGA 8812/1/2/2709). Clark responded sympathetically and pragmatically: writing he was ‘more than ever shocked that you did not receive a higher diploma’, purchasing another of her works for £25, and offering advice re the massing of light and dark areas in a way that the subject can be easily grasped—suggesting she look to Sickert in this regard (Clark to Grunwald, 10 July 1952, TGA 8812/1/2/2710).

Grunwald spent that summer working at a National Union of Students (NUS) camp at Catfield, Norfolk, picking fruit and sketching landscapes in her spare time, afterwards painting landscapes at Essex and Suffolk (Grunwald to Clark, 17 July 1952 and 22 August 1952, TGA 8812/1/2/2711 and 8812/1/2/2713).

She commenced teaching in February 1953, initially at a private school—possibly Ashby Secondary Modern Girls’ School at Scunthorpe, Lincolnshire, for which Clark agreed to supply a written reference while hoping she would secure a more sympathetic post (Clark to Grunwald, 17 December 1952, TGA 8812/1/2/2717). After six months she moved, in September 1953, to Fort Pitt Technical School at Chatham in Kent, where she found the art department facilities to be excellent though she struggled to find sufficient time to paint (Grunwald to Clark, 22 November 1953, TGA 8812/1/2/2718). During the 1960s and 1970s Grunwald taught art at Paddington and Maida Vale High School (originally an all-girls school, it amalgamated with North Paddington School in 1972 to become the mixed-sex Paddington School; see T F T Baker, Diane K Bolton and Patricia E C Croot, ‘Paddington: Education’, in A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 9, Hampstead, Paddington, ed. C R Elrington (London, 1989), pp. 265-271. British History Online). There her students included the future Turner Prize winner Lubaina Himid (information from Louise Shalev née Gordon via Monica Bohm-Duchen, 11 May 2022). Among the many student exhibitions that she organised for the school was People to People, ‘which set out to create mutual understanding and interest among different peoples’ (‘People to People Art’, Marylebone Mercury, London, 1 December 1967, p. 4). While she later referred to this aspect of her work as ‘the dreaded teaching’, she appreciated its ‘beneficial side — simplifying ideas, formulating and observing things which one had perhaps neglected as a student’ (Grunwald to Clark, 11 October 1976, TGA 8812/1/3/1235/1). She remained as art mistress at Paddington School until the late 1970s.

In addition to teaching, Grunwald also painted murals. An extension to St Thomas of Canterbury Church in Canterbury, Kent, in 1963, saw the construction of a new chapel on the north side of the church, for which Grunwald received her first major commission. The Canterbury Saints depicts Christ surrounded by a dozen saints, including St Augustine of Canterbury (founder of the Christian church in southern England) and Pope Gregory, as well as nuns and monks, all set within a trompe l’oeil architectural structure. Grunwald later glimpsed her mural on television, which prompted her to think further about ‘the three fold unity of the sound, structure of building + drawing’ and resulted in a new series of work that she exhibited in 1975 (Grunwald to Clark, 10 March 1975, TGA 8812/1/3/1234). She also painted murals for the Americana club in Croydon, London, c. 1975 (as mentioned briefly in The Stage and Television Today, 18 September 1975, p. 6).

Helen and Lillian Grunwald eventually left the Abbey in the mid-1970s, moving to a flat at 48 Blomfield Road, Little Venice, where they remained for the rest of their lives (their presence at the Abbey as late as 1965 is documented in the London Metropolitan Archives, Electoral Registers, Barnet, England, LCC/PER/B/2986). They continued to live together until Lillian’s death in 1982. Mother and daughter shared many of the same interests, both becoming adherents of the esoteric philosophy group centred about George Gurdjieff (who died in Paris in 1949) and his London followers, particularly the group centred around the Jungian psychoanalyst Maurice Nicholl (1884–1953). Another friend of Grunwald's and Fitzpayne's, also associated with the Nicholl group, was Dorothy King who headed the South London Art Gallery. Mary Alice Fitzpayne sketched Helen and Lillian performing what she referred to as ‘Grecian’ dancing, in long robes, to the sounds of an accompanying gramaphone; the sketches remain in Fitzpayne’s possession. The dancing was likely inspired by Gurdjieff's 'sacred movements' or Rudolf Steiner's 'Eurythy', which is taught at Waldorf schools worldwide.

Lillian died in January 1982; Helen would survive her by only six years (General Register Office, UK, vol. 15, pp. 1479, 2323).

Grunwald’s love of music—particularly Bach—drew her to the Tilford Choir and Orchestra, which she regularly sketched throughout the 1960s and ‘70s. In June 1975 she exhibited these pen and ink sketches along with large, abstracted paintings in the porch and baptistry of St George’s Church, Hanover Square, W1, coinciding with the Tilford Bach Festival Choir and Orchestra’s third annual week of Bach in London (Janet Watts, ‘Colouring Bach’, The Guardian, 25 June 1975, p. 11, article courtesy BURU). She also executed a number of what she termed ‘decorations’ for the Tilford Bach Choir, which were used, for instance, for their 1976–77 season program. Clark thought them ‘beautifully drawn, but … You are best at drawings of living people, like the Orchestra, and the Tilford Bach Choir, and they do not gain by being made into decorations’, suggesting again she consider going into book illustration (Clark to Grunwald, 14 October 1976, TGA, 8812.1.3.1236). She again exhibited at St George’s, Hanover Square, for the third London Handel Festival (27 April to 4 May 1980). In the month before the exhibition, Sir Ernst Grombrich visited Grunwald at her Blomfield Road studio to inspect the work—about which he had agreed to write for the festival program. Grunwald reported Gombrich’s visit to Clark: ‘Sir Ernst says Ruskin would have liked my work—& that I could do stained glass design’ (Grunwald to Clark, 27 March 1980, TGA, 8812.1.3.1237). In May 1985 she exhibited new paintings and drawings under the title ‘Bach in Splendour’ at St Anne and St Agnes on Gresham Street in the city of London (The Times, London, 16 April 1985, p. 36).

The canal-side scenes and streets of old houses around Little Venice became an increasing focus for her work in the 1970s and she became well-known in local artistic circles, even initiating ‘an experimental “group” about once every four weeks, when a few artists and musicians meet, to paint, or write together, or make music, or even just relax!’ (Grunwald to Fitzpayne, 8 October 1976, private collection). She also experimented with lithography and linocut printmaking at this time. In 1978 the Marylebone Local History Room acquired forty-two of drawings and lithographs of north Westminster scenes and exhibited them at Marylebone Library (Westminister City Libraries, Annual Report of the City Librarian, 1978-79, p. 7). In November 1980 she held a second exhibition of drawings of Marylebone, Mayfair and Paddington at Marylebone Library. Studies of old houses—including Handel’s home in Brock Street—were interspersed with market studies (Noreen Caffrey, ‘Historic scenes captured in local exhibition’, Marylebone Mercury, London, 28 November 1980, p. 11, illustrated). An exhibition in the visitor’s gallery of the Stock Exchange, in 1984, was titled Helen Mary Grunwald: the changing, changeless city; drawings, paintings, prints, indicating her preoccupations with her physical environs. A vignette drawing of the Saint Mary Magdalene Church, with canal boats moored in the foreground, near to her home in Blomfield Road, would constitute her personal letterhead in the 1980s.

Her final major commission, received in 1985 and part-funded by Westminster Council, was to paint a series of Byzantine-style murals for the apse of a 130-year-old Russian Chapel at 32 Welbeck Street, Marylebone (‘A Russian Chapel in Marylebone’, Ecclesiological Society Newsletter, no. 16, April 1985, p. 11). The chapel had been unused for many years and the building’s then tenants, the Variety Club of Great Britain, who had applied without success to alter the building, accepted the council’s offer to meet half the cost of restoring the chapel. Grunwald’s commission formed part of the restoration process. Local newspapers compared Grunwald to Michelangelo, as she worked on scaffolding for six months to complete the work. ‘The main theme of the murals’, she initially told a reporter, ‘is healing the sick because Variety Club do a lot of charitable work in this field especially with children’ (Graham James, ‘Restored to glory’, Paddington Mercury, London, 24 January 1986, p. 24, illustrated). However, the Association of Jewish Refugees in Britain later reported that Grunwald chose the theme of human suffering and resurrection, with many parallels to Nazi persecution and racial intolerance, and a depiction of the gas chambers (C.A. ‘Helen Grunwald's Murals’, ARJ Information, vol. XLI, no. 12, Dec 1986, p. 6). When unveiled in mid-1986, the Variety Club reportedly ‘reacted in horror’, claiming Grunwald ‘had got carried away with her own enthusiasm’ and that the religious atmosphere was not ‘conducive to work’ (‘‘Niet, niet’, to work of art’, Marylebone Mercury, London, 14 August 1986, p. 1). Despite the work being praised by Canon David, Bishop of Norwich Cathedral and chairman of Art in Churches, the tenants erected screens to block the view of the murals, which were eventually painted over (Barlett School of Architecture, University College London, Survey of London: vols. 51 and 52, South-East Marylebone, London: UCL, 2017, chapter 14, p. 23 of draft version, check page ref for printed publication).

Helen Grunwald died of a cerebral infarction and vasultis, 21 June 1988, aged 63, at St Mary's Hospital, Westminster (General Register Office, UK, 1988, vol. 15, p. 1479, and Death certificate, registered City of Wesminster, 14 June 1988, application no. 12179018/1, QBDAC 347492). She was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery.

Her will requested she be buried according to the rites of the Church of England, but with the service shared with a Catholic priest, a Buddhist, and a Rabbi. While she left no next-of-kin, she made generous provision for the care of her cat and left her flat to a friend, Miss Marjorie Wardle. The remainder of her estate was split between various named charities and her artworks sold. The final paragraph of her will read: "May religion cease to be a cause of division and may our trickle of endeavour and love penetrate the chemical waste land of inner and outer destruction and desolation" (information kindly supplied by Catherine Hill, The National Archives, Kew, 24 April 2023).

Jane Eckett

31 May 2022

(updated 25 April 2023)

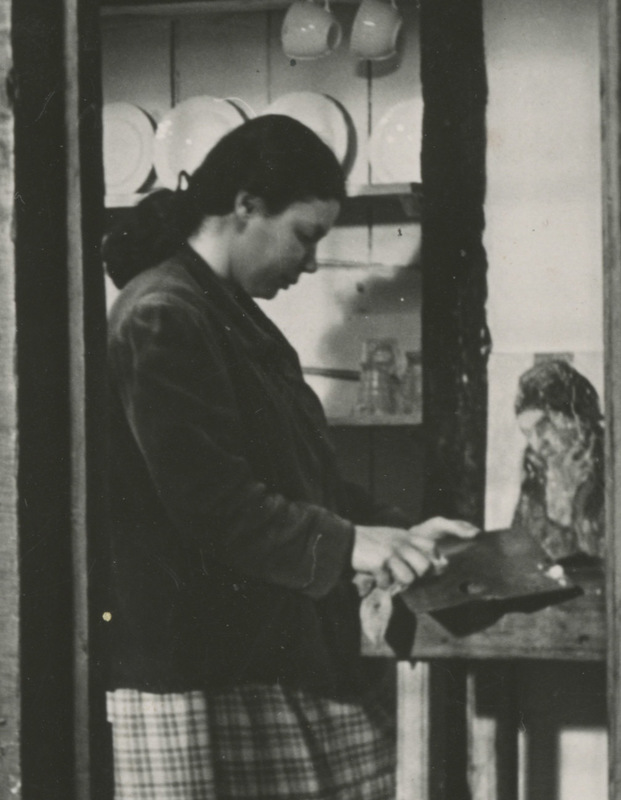

Photograph (i)

Helen Grünwald in the Abbey Cottage, c. 1950, attributed to Picture Post, private collection, England

Date submitted

10 August 2021

Date modified

28 January 2026

Collection

Citation

“Helen Grünwald ARCA (1925–1988),” The Abbey Art Centre Digital Repository, accessed February 6, 2026, https://omeka.cloud.unimelb.edu.au/abbey-art-centre/items/show/991.