Helen Marshall (1908–1996)

Identifier

127.0000

Title

Helen Marshall (1908–1996)

Type

person

Subject

Marshall, Helen, 1908–1996.

Relation

Contributor

Jane Eckett

Birth Date

14 March 1908

Birthplace

Drumavally, Bellarena, Co. Londonderry, Northern Ireland

Death Date

March 1996

Place of death

Glebe, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Occupation

painter, textile artist

Biography

Born Helen Marshall Allen, in Drumavally, Magilligan, in the Bellarena district of Northern Ireland, she was the eldest of nine children born to Bessie and James Allen. Her mother hailed from Govan in Scotland while her father, some twenty years older, worked variously as a fisherman and stonemason. James Allen had three young children from a previous marriage, and he and Bessie also adopted two neighbouring children. Family stories credit the over-crowded household as being the chief reason for Marshall’s emigration in September 1926 to Australia, alone, at the age of eighteen, on the migrant ship the Baradine (though an aunt already in Melbourne probably encouraged the move).

Two years later Marshall married Stephen Carlisle Walton, a sign-writer by trade, and with him had three children. Between 1928 and 1950 they lived at various addresses around Brighton and Blackrock along Port Phillip Bay. According to Phillip Martin’s unpublished notes, during these years, in addition to raising a family, she worked in landscape gardening and lectured in child psychology.

In 1947, on Alan Warren’s recommendation, Marshall joined George Bell’s Sunday morning painting classes (Felicity St John Moore, 'Artist drew on innocent dreams', The Australian, 24 April 1996, p. 10). Her earliest extant works are three oils of gardens and coastal heathlands, dating to 1948-50, painted in an energetic post-impressionist mode (Our Back Garden, 1948; Blackrock Foreshore, 1949; Untitled (landscape with three trees and track), c. 1948-1950). In the catalogue to the exhibition Classical Modernism: The George Bell Circle, Felicity St John-Moore noted Marshall’s ‘conspicuous exuberance’ and ‘tendency towards personal expression’. Through the George Bell circle she befriended Arthur Boyd, John Perceval, Danila Vassilieff (who reputedly referred to her as ‘my woman’) and Stacha Halpern with whom she worked on ceramics. She also regularly visited John and Sunday Reed at Heide.

Marshall returned to Bellarena with her youngest child Stephen Walton (then aged two), sailing on the Otranto and arriving at London on 24 July 1950. She gave their intended address as her parents' address: Lenamore, Bellarena, Co. Derry, Northern Ireland. The trip precipitated a dramatic shift in her painting both in subject and style. Henceforth she channelled a child-like and deeply personal vision of cottages, farm implements, donkeys, birds, fish, boats, church spires and pagan shrines, painted with expressionistic vigour in rich hallucinatory colours. A handful of works from this visit, such as Lennamore, Bellarena, 1950, include a hand-cranked grinding stone that became a recurrent motif—a talismanic memory of her Northern Irish childhood.

Soon afterwards Marshall arrived at the Abbey Art Centre, New Barnet, on London’s outskirts. There she met the young Tachiste painter, Phillip Martin, who, with the encouragement of another Abbey resident, the Scottish painter Alan Davie, was then making small black and white monotypes, and dense gestural oils and collages. No works from her time at the Abbey have been traced. Early in 1951 Marshall and Martin left the Abbey and by May were living on a disused barge, The Sheila, at Thames Ditton. They began there a series of joint works in marine paints and collage, united in their visionary poetics, which would continue for the rest of their lives.

In August 1951 the pair travelled to Paris then on to Schruns (Austria), Genova and Florence, where they held their first joint exhibition at Galeria Numero. Many of Marshall’s watercolours from this time are painted on crepe-paper hand towel from train station restrooms, the paint bleeding into its crevices like blotting paper. In Florence they learnt their houseboat in London had burnt, destroying all their work (hence the absence of any Abbey works, for Marshall at least). A period of extreme hardship ensued. Retreating to Tourettes-sur-Loup for the winter, they met Alphonse Chave of Galerie Les Mages, in Vence, who gave them an exhibition and, reputedly on the recommendation of Marc Chagall, purchased all of Marshall’s exhibits.

Throughout the 1950s Marshall and Martin orbited with astonishing frequency between Paris, Positano, Forio d’Ischia (off Naples, where their daughter, printmaker Seraphina Martin, was born in 1954), Florence, Aix-en-Provence, Mallorca, Alicante and Formentera, as well as a summer in Connemara. Along the way they befriended the likes of Alan Sillitoe in Spain and Roberto Matta, Andre Masson, Karel Appel and Pierre Alechinsky in Paris.

Mixing in Surrealist and Art Informel circles, Marshall experimented with frottage: placing cardboard cut-outs under a thin sheet of paper, which was rubbed with crayon to produce a ghostly trace. Her visual storehouse also grew: fishing harbours, a salt train engine, and an enigmatic black goddess joined Marshall’s pervading Irish imagery and memories of ‘her land’—Bellarena.

Among the curators and critics who respected Marshall’s deeply personal lexicon was Arnold Rüdlinger, director of the Kunsthalle Bern, who gave Marshall and Martin a significant exhibition in 1953 alongside Viera da Silva. In the catalogue Rüdlinger attributed the childlike quality of Marshall’s work to their origins in ‘fantasy, which is located in the world of dreams, fairy tales and legends.’ He might have added that this fantasy was rooted in Irish folklore. Alain Jouffroy was another supporter. He and Jean-Jacques Lebel included Marshall and Martin in the first Anti-Procès ‘manifestation collective’ (an exhibition, a happening and a manifesto), in 1960, alongside César, Hundertwasser, Wifredo Lam and Matta among others. Marshall’s evasion of neat nationalist categories, her lack of materialism or concern for the commercial art world’s social mores, and her pacifism were consistent with the Anti-Procès group’s philosophy and their condemnation of French state violence in Algeria.

In 1962 Marshall and Martin, along with the children Stephen and Seraphina, travelled to India to join the Sri Aurobindo ashram in Pondicherry. Marshall’s work registered this new beginning: her palette brightened and her compositions grew more elaborate, with overlapping elements occupying the entire surface. Offering to Savitri, 1964, with its collaged scraps of Indian wrapping paper, foil and paper doilies, and To Awakening, 1965, in the National Gallery of Victoria collection, indicate this new direction. India represented for Marshall the twin pole of Ireland in terms of sustaining her visual and spiritual storehouse.

For the next seven years she and Martin spent part of each year at Pondicherry, returning either to Paris, London or Brussels, where they spent nearly two years and had a major joint retrospective at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in 1966. In 1968, they attended the inauguration of Auroville, a utopian ‘universal city’ based on the vision of Sri Aurobindo and The Mother, commemorating the occasion with an exhibition at the Jehangir Gallery—Mumbai’s foremost modern gallery.

After India they briefly return to Australia, 1969-70, to reunite with Marshall’s family who had since emigrated from Ireland. In Sydney a critically acclaimed exhibition of over 200 of Martin and Marshall’s works inaugurated Gisella Scheinberg’s Holdsworth Gallery (see Ruth Faerber's review, 'Art. Coherent exhuberance', The Australian Jewish Times, Sydney, 2 October 1969, p. 4), while in Melbourne Georges Mora of Tolarno was supportive (for six months they lived next door to Mirka Mora in St Kilda).

But Europe drew them back: first to Milan, in 1971, and then Bellagio on Lake Como where they acquired their first home in exchange for a large collection of Martin’s paintings. Over the next six years they continued to travel—spending months at a time in Paris, Milan, Roscoff, Brittany and Gstaad, Switzerland.

In 1979 they returned to Sydney permanently, purchasing a Victorian terrace-house in Glebe, which quickly filled with their paintings, relief sculptures and Marshall’s hand-stitched ‘banners’ or wall hangings. Even still they continued to exhibit in Europe, Marshall having solo shows with Galerie Gammel Strand, Copenhagen, in 1980, and Galerie Riedel, Paris, in 1987, while in Sydney she had further solo exhibitions at the Art of Man Gallery, 1980 (see Ruth Faerber's review, The Australian Jewish Times, Sydney, 22 May 1980, p. 16); Beasts and other animals at the Irving Sculpture Gallery, 1985; Richard King Gallery, 1987; and Coventry Gallery, 1991 and 1994. Elwyn Lynn, among others, appreciated Marshall’s ‘spritely, playful … presentation of people, birds and flowers all in ecstatic togetherness’ (Elwyn Lynn, The Weekend Australian, 20-21 June 1987). Marshall died in 1996, aged 88, and Martin devoted much of the next eighteen years to documenting her career before his own death in 2014.

Jane Eckett

November 2019

Two years later Marshall married Stephen Carlisle Walton, a sign-writer by trade, and with him had three children. Between 1928 and 1950 they lived at various addresses around Brighton and Blackrock along Port Phillip Bay. According to Phillip Martin’s unpublished notes, during these years, in addition to raising a family, she worked in landscape gardening and lectured in child psychology.

In 1947, on Alan Warren’s recommendation, Marshall joined George Bell’s Sunday morning painting classes (Felicity St John Moore, 'Artist drew on innocent dreams', The Australian, 24 April 1996, p. 10). Her earliest extant works are three oils of gardens and coastal heathlands, dating to 1948-50, painted in an energetic post-impressionist mode (Our Back Garden, 1948; Blackrock Foreshore, 1949; Untitled (landscape with three trees and track), c. 1948-1950). In the catalogue to the exhibition Classical Modernism: The George Bell Circle, Felicity St John-Moore noted Marshall’s ‘conspicuous exuberance’ and ‘tendency towards personal expression’. Through the George Bell circle she befriended Arthur Boyd, John Perceval, Danila Vassilieff (who reputedly referred to her as ‘my woman’) and Stacha Halpern with whom she worked on ceramics. She also regularly visited John and Sunday Reed at Heide.

Marshall returned to Bellarena with her youngest child Stephen Walton (then aged two), sailing on the Otranto and arriving at London on 24 July 1950. She gave their intended address as her parents' address: Lenamore, Bellarena, Co. Derry, Northern Ireland. The trip precipitated a dramatic shift in her painting both in subject and style. Henceforth she channelled a child-like and deeply personal vision of cottages, farm implements, donkeys, birds, fish, boats, church spires and pagan shrines, painted with expressionistic vigour in rich hallucinatory colours. A handful of works from this visit, such as Lennamore, Bellarena, 1950, include a hand-cranked grinding stone that became a recurrent motif—a talismanic memory of her Northern Irish childhood.

Soon afterwards Marshall arrived at the Abbey Art Centre, New Barnet, on London’s outskirts. There she met the young Tachiste painter, Phillip Martin, who, with the encouragement of another Abbey resident, the Scottish painter Alan Davie, was then making small black and white monotypes, and dense gestural oils and collages. No works from her time at the Abbey have been traced. Early in 1951 Marshall and Martin left the Abbey and by May were living on a disused barge, The Sheila, at Thames Ditton. They began there a series of joint works in marine paints and collage, united in their visionary poetics, which would continue for the rest of their lives.

In August 1951 the pair travelled to Paris then on to Schruns (Austria), Genova and Florence, where they held their first joint exhibition at Galeria Numero. Many of Marshall’s watercolours from this time are painted on crepe-paper hand towel from train station restrooms, the paint bleeding into its crevices like blotting paper. In Florence they learnt their houseboat in London had burnt, destroying all their work (hence the absence of any Abbey works, for Marshall at least). A period of extreme hardship ensued. Retreating to Tourettes-sur-Loup for the winter, they met Alphonse Chave of Galerie Les Mages, in Vence, who gave them an exhibition and, reputedly on the recommendation of Marc Chagall, purchased all of Marshall’s exhibits.

Throughout the 1950s Marshall and Martin orbited with astonishing frequency between Paris, Positano, Forio d’Ischia (off Naples, where their daughter, printmaker Seraphina Martin, was born in 1954), Florence, Aix-en-Provence, Mallorca, Alicante and Formentera, as well as a summer in Connemara. Along the way they befriended the likes of Alan Sillitoe in Spain and Roberto Matta, Andre Masson, Karel Appel and Pierre Alechinsky in Paris.

Mixing in Surrealist and Art Informel circles, Marshall experimented with frottage: placing cardboard cut-outs under a thin sheet of paper, which was rubbed with crayon to produce a ghostly trace. Her visual storehouse also grew: fishing harbours, a salt train engine, and an enigmatic black goddess joined Marshall’s pervading Irish imagery and memories of ‘her land’—Bellarena.

Among the curators and critics who respected Marshall’s deeply personal lexicon was Arnold Rüdlinger, director of the Kunsthalle Bern, who gave Marshall and Martin a significant exhibition in 1953 alongside Viera da Silva. In the catalogue Rüdlinger attributed the childlike quality of Marshall’s work to their origins in ‘fantasy, which is located in the world of dreams, fairy tales and legends.’ He might have added that this fantasy was rooted in Irish folklore. Alain Jouffroy was another supporter. He and Jean-Jacques Lebel included Marshall and Martin in the first Anti-Procès ‘manifestation collective’ (an exhibition, a happening and a manifesto), in 1960, alongside César, Hundertwasser, Wifredo Lam and Matta among others. Marshall’s evasion of neat nationalist categories, her lack of materialism or concern for the commercial art world’s social mores, and her pacifism were consistent with the Anti-Procès group’s philosophy and their condemnation of French state violence in Algeria.

In 1962 Marshall and Martin, along with the children Stephen and Seraphina, travelled to India to join the Sri Aurobindo ashram in Pondicherry. Marshall’s work registered this new beginning: her palette brightened and her compositions grew more elaborate, with overlapping elements occupying the entire surface. Offering to Savitri, 1964, with its collaged scraps of Indian wrapping paper, foil and paper doilies, and To Awakening, 1965, in the National Gallery of Victoria collection, indicate this new direction. India represented for Marshall the twin pole of Ireland in terms of sustaining her visual and spiritual storehouse.

For the next seven years she and Martin spent part of each year at Pondicherry, returning either to Paris, London or Brussels, where they spent nearly two years and had a major joint retrospective at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in 1966. In 1968, they attended the inauguration of Auroville, a utopian ‘universal city’ based on the vision of Sri Aurobindo and The Mother, commemorating the occasion with an exhibition at the Jehangir Gallery—Mumbai’s foremost modern gallery.

After India they briefly return to Australia, 1969-70, to reunite with Marshall’s family who had since emigrated from Ireland. In Sydney a critically acclaimed exhibition of over 200 of Martin and Marshall’s works inaugurated Gisella Scheinberg’s Holdsworth Gallery (see Ruth Faerber's review, 'Art. Coherent exhuberance', The Australian Jewish Times, Sydney, 2 October 1969, p. 4), while in Melbourne Georges Mora of Tolarno was supportive (for six months they lived next door to Mirka Mora in St Kilda).

But Europe drew them back: first to Milan, in 1971, and then Bellagio on Lake Como where they acquired their first home in exchange for a large collection of Martin’s paintings. Over the next six years they continued to travel—spending months at a time in Paris, Milan, Roscoff, Brittany and Gstaad, Switzerland.

In 1979 they returned to Sydney permanently, purchasing a Victorian terrace-house in Glebe, which quickly filled with their paintings, relief sculptures and Marshall’s hand-stitched ‘banners’ or wall hangings. Even still they continued to exhibit in Europe, Marshall having solo shows with Galerie Gammel Strand, Copenhagen, in 1980, and Galerie Riedel, Paris, in 1987, while in Sydney she had further solo exhibitions at the Art of Man Gallery, 1980 (see Ruth Faerber's review, The Australian Jewish Times, Sydney, 22 May 1980, p. 16); Beasts and other animals at the Irving Sculpture Gallery, 1985; Richard King Gallery, 1987; and Coventry Gallery, 1991 and 1994. Elwyn Lynn, among others, appreciated Marshall’s ‘spritely, playful … presentation of people, birds and flowers all in ecstatic togetherness’ (Elwyn Lynn, The Weekend Australian, 20-21 June 1987). Marshall died in 1996, aged 88, and Martin devoted much of the next eighteen years to documenting her career before his own death in 2014.

Jane Eckett

November 2019

Bibliography

Arnold Rüdlinger, Vieira da Silva, Phillip Martin, Helen Marshall, Bern, Switzerland: Kunsthalle Bern, 7 February – 8 March 1953.

Alain Jouffroy, Helen Marshall, Phillip Martin: peintures, collages, gouaches, oeuvres jointes, 1950-1966, Brussels, Belgium: Palais des beaux-arts de Bruxelles, 14–26 April 1966.

Nevill Drury, New art five: profiles in contemporary Australian art, Roseville East, NSW: Craftsman House, 1991.

Felicity St. John Moore, Classical modernism: the George Bell circle, Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 1992.

Felicity St John Moore, 'Artist drew on innocent dreams [obituary of Helen Marshall]', The Australian, 24 April 1996, p. 10.

Phillip Martin, unpublished synopsis of the life and career of Helen Marshall (1918–1996), two-page manuscript, c. 1996, Sydney: estate of Phillip Martin and Helen Marshall.

Jane Eckett, 'Helen Marshall: Return to Beginning', Artist Profile, no. 49, November 2019, pp. 136-9.

Alain Jouffroy, Helen Marshall, Phillip Martin: peintures, collages, gouaches, oeuvres jointes, 1950-1966, Brussels, Belgium: Palais des beaux-arts de Bruxelles, 14–26 April 1966.

Nevill Drury, New art five: profiles in contemporary Australian art, Roseville East, NSW: Craftsman House, 1991.

Felicity St. John Moore, Classical modernism: the George Bell circle, Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 1992.

Felicity St John Moore, 'Artist drew on innocent dreams [obituary of Helen Marshall]', The Australian, 24 April 1996, p. 10.

Phillip Martin, unpublished synopsis of the life and career of Helen Marshall (1918–1996), two-page manuscript, c. 1996, Sydney: estate of Phillip Martin and Helen Marshall.

Jane Eckett, 'Helen Marshall: Return to Beginning', Artist Profile, no. 49, November 2019, pp. 136-9.

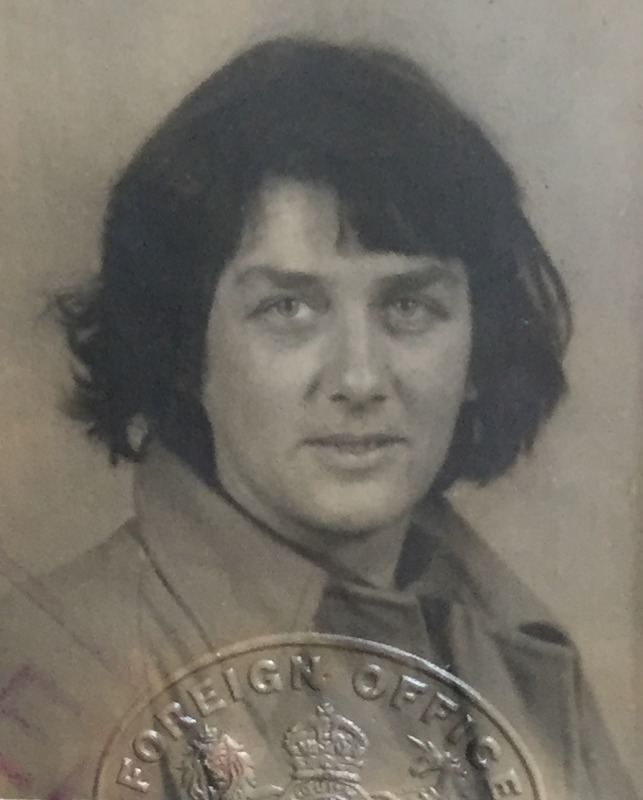

Photograph (i)

Helen Marshall, identity photograph pasted in her British passport, issued in France c. 1951–55, courtesy artist's estate

Date submitted

10 August 2021

Date modified

16 August 2021

Collection

Citation

“Helen Marshall (1908–1996),” The Abbey Art Centre Digital Repository, accessed January 1, 2026, https://omeka.cloud.unimelb.edu.au/abbey-art-centre/items/show/999.