Lotte Reiniger (1899–1982)

Identifier

131.000

Title

Lotte Reiniger (1899–1982)

Type

person

Subject

Reiniger, Lotte, 1899–1982.

Koch, Carl, 1892–1963.

Koch, Carl, 1892–1963.

Relation

Contributor

Sheridan Palmer

Birth Date

2 June 1899

Birthplace

Berlin-Charlottenburg, Germany

Death Date

19 June 1981

Place of death

Dettenhausen, Tübingen, Germany

Occupation

Pioneer film maker, film director, animator, puppeteer, book illustrator

Biography

Born Charlotte Eleonore Elisabeth Reiniger in Berlin in 1899. As a child she learned scherenschnitte, the art of cutting paper designs with scissors (Reiniger, 1936, p. 13; Sterritt, 2020, p. 399). Later she became deeply involved in the cultural and intellectual avant-garde world of pre-World War II Berlin, and her earliest films were made at the Institut für Kulturforschung (Institute for Cultural Research) in Berlin. Her friends included Bertolt Brecht and Fritz Lang and she worked with prominent young intellectuals such as Berthold Bartosch, a collaborator on many of her films during the 1920s, and Carl Koch, who had studied art history and philosophy and was involved in producing educational films and documentaries for the Institute (Guerin and Mebold, 2016). Koch was interested in the technical aspects of filmmaking and experimenting with animation and was a perfect collaborator with Reiniger. Reiniger and Koch were married in the Berlin-Schonberg registrar office on 6 December 1921 (Grace, 2017, chapter 2).

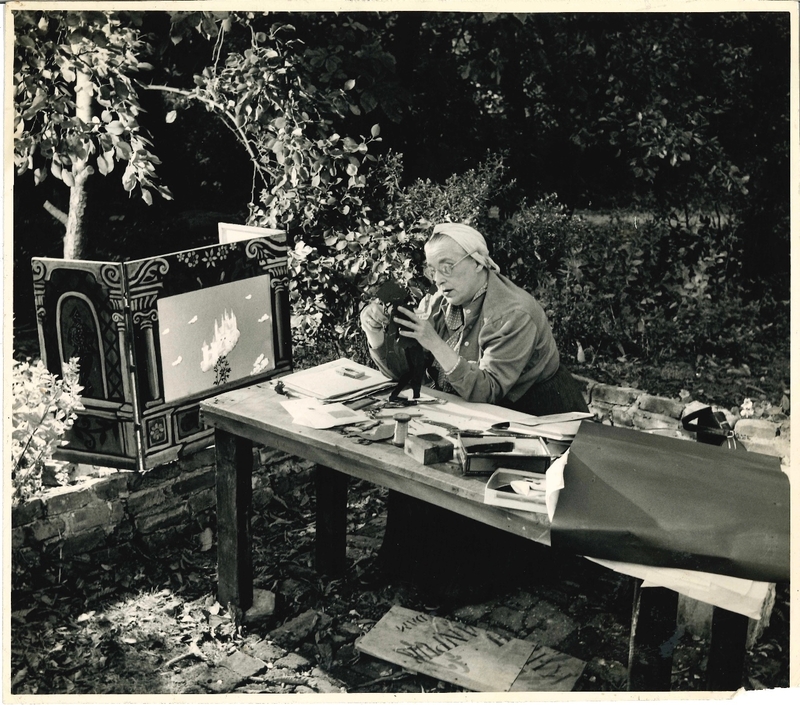

Reiniger and Koch’s early films ranged from brief shorts to Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed (The Adventures of Prince Achmed) (1923-6), which is widely claimed as the first full-length animated feature film and considered a milestone of cinema history. One of Reiniger’s most important innovations was the multiplane camera, which she called a tricktisch (trick table), explaining its use as follows: ‘Figures and backgrounds are laid out on a glass table. A strong light from underneath makes the wire hinges disappear and throws up the black figures in relief. The camera hangs above … looking down at the picture arranged below’ (Reiniger, 1936, p. 14).

Reiniger wrote screenplays for her films and worked as a major contributor on several of Koch’s live action films, including wartime Italian productions of Tosca (1941, co-directed by Koch and Jean Renoir) and La Signora dell’Ovest (The Lady of the West) (1941-2) (Guerin and Mebold, 2016).

Having studied traditional silhouette representation of the human figure, supplemented by her knowledge of ancient Eastern and Oriental performance traditions, Reiniger also designed costumes and sets for theatre and opera, staged puppet shows and shadow plays, illustrated books, newspapers, and magazines. She was an accomplished artist in ink and watercolor as well as a writer and a poet, and she gave public lectures on animation and experimental film history. Classical music was an important aspect of her films and she collaborated with composers Kurt Weill, Paul Dessau, Benjamin Britten and Peter Gellhorn (Guerin and Mebold, 2016).

Although not Jewish, Reiniger and Koch had many Jewish friends and closely identified with leftist politics, making life in Germany under the Nazi regime difficult (Sterritt, 2020, p. 399). In November 1935 they left for England and over the next four years lived variously in London, Paris and Rome. In England Reiniger made short films for the GPO Film Unit. At the outbreak of war, in September 1939, Reiniger re-joined Koch in Rome, where he was working with Jean Renoir on Tosca. In September 1943, with the situation in Italy worsening, they were advised by the embassy to leave without delay, and moved from Rome to Venice, then back to Berlin, where Reiniger’s ill mother was living alone. In Berlin, Reiniger unexpectedly received a film commission, Die Goldene Gans (1944-7), which provided an income, but food and power shortages made living difficult.

In September 1948 she and Koch visited Alexander Kardan (with whom they had earlier collaborated on Prinzen Achmed), staying with him in London until November, when Reiniger had to return to Berlin. Reiniger left Germany permanently on 31 January 1949, re-joining Koch in London where they lived for some months at 236 Latimer Court, Hammersmith, W6, before moving in late 1949 to Wilton Cottage, Kings Road, Chalfont St Giles, Buckinghamshire (Happ, 2004, p. 67).

In London they received further commissions from the GPO Film Unit (renamed after the war the Crown Film Unit, part of the Central Office of Information), making many advertising films for them such as Post Early for Christmas (1950). Other promotional films included The Dancing Fleece (also known as Wool Ballet), for the English Department of Labor, and Grain Harvest (1950) for the Ministry of Agriculture.

In 1952 they established their own company Primrose Productions, with Viviana Milroy as producer and the financial backing of Louis Hagen Junior. Primrose Productions was primarily concerned with producing animated silhouette fairy tale films for children. Between 1953 and 1954 twelve such were produced and the 1950s would represent a highwater mark in Reiniger’s long career. These were made on a tricktisch that Hagen bought for Reiniger, and which was installed at the Abbey Art Centre, New Barnet, where Reiniger and Koch moved to in 1952.

Whitney Grace writes that ‘Reiniger and Koch were welcomed at the Abbey Arts Centre, finding that being around fellow artists helped inspire their own work’ (Grace, 2017, chapter 7). Reiniger later told Alfred Happ that the Abbey Art Center residents ‘… live in their separate households, but close enough to inspire one another. The museum provided me with a number of artworks from different parts of the world, it’s not only ideas, but a widening creative atmosphere’ (Reiniger cited in Happ, 2004, p. 82). When William Ohly, the founder of the Abbey, died in 1955, Reiniger painted a memorial window of St Francis of Assisi for the Abbey tithe barn, where it remains to this day.

Reiniger became a mentor to a younger Abbey resident, the English-born sculptor Peter King, whose experimental animated film, 13 Cantos of Hell (1955), was made using Reiniger’s shadow puppet techniques. Reiniger and Koch were also godparents to King’s first two children, Michael and Janet, born at the Abbey in 1953 and 1954 respectively. New Zealander Daryl Hill, who worked as assistant to Henry Moore during the mid-1950s alongside Lenton Parr and who was a probable visitor to the Abbey, became interested in film at this time through Reiniger and Koch, later citing their influence on his own experimental filmmaking in Australia in the 1960s (Laurie Thomas, ‘Those who are alone’ [interview with Daryl Hill], The Australian, 22 July 1967, p. 8). Given that Reiniger and Koch were two of the Abbey’s longest term residents—Koch lived there up until his death in 1963 while Reiniger remained until 1980—it is likely that other Abbey residents also came within their circle of influence.

After Koch’s death, Reiniger retired from film making but continued lecturing at film festivals and workshops in Europe and Canada during the 1970s. Her tricktisch lay disassembled in parts in her room at the Abbey until early 1980, when the director of the Düsseldorf Stadtmuseum, Hartmut W. Redottėe, wrote to Reiniger and asked to purchase it for the museum. After agreeing on a price, he flew to England to oversee the table’s packaging and removal from the Abbey and while there, observing Reiniger’s sadness, spontaneously invited her to come to Düsseldorf and make a film on the table at the museum as part of an exhibition he was organising for that September. The result, Düsselchen und die vier Jahreszeiten (Düsselchen and the Four Seasons), would be her final film. Reiniger left the Abbey permanently that year, moving to Germany where she lived her final year with the Happ family at Dettanhausen, Tübingen.

Sheridan Palmer

Reiniger and Koch’s early films ranged from brief shorts to Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed (The Adventures of Prince Achmed) (1923-6), which is widely claimed as the first full-length animated feature film and considered a milestone of cinema history. One of Reiniger’s most important innovations was the multiplane camera, which she called a tricktisch (trick table), explaining its use as follows: ‘Figures and backgrounds are laid out on a glass table. A strong light from underneath makes the wire hinges disappear and throws up the black figures in relief. The camera hangs above … looking down at the picture arranged below’ (Reiniger, 1936, p. 14).

Reiniger wrote screenplays for her films and worked as a major contributor on several of Koch’s live action films, including wartime Italian productions of Tosca (1941, co-directed by Koch and Jean Renoir) and La Signora dell’Ovest (The Lady of the West) (1941-2) (Guerin and Mebold, 2016).

Having studied traditional silhouette representation of the human figure, supplemented by her knowledge of ancient Eastern and Oriental performance traditions, Reiniger also designed costumes and sets for theatre and opera, staged puppet shows and shadow plays, illustrated books, newspapers, and magazines. She was an accomplished artist in ink and watercolor as well as a writer and a poet, and she gave public lectures on animation and experimental film history. Classical music was an important aspect of her films and she collaborated with composers Kurt Weill, Paul Dessau, Benjamin Britten and Peter Gellhorn (Guerin and Mebold, 2016).

Although not Jewish, Reiniger and Koch had many Jewish friends and closely identified with leftist politics, making life in Germany under the Nazi regime difficult (Sterritt, 2020, p. 399). In November 1935 they left for England and over the next four years lived variously in London, Paris and Rome. In England Reiniger made short films for the GPO Film Unit. At the outbreak of war, in September 1939, Reiniger re-joined Koch in Rome, where he was working with Jean Renoir on Tosca. In September 1943, with the situation in Italy worsening, they were advised by the embassy to leave without delay, and moved from Rome to Venice, then back to Berlin, where Reiniger’s ill mother was living alone. In Berlin, Reiniger unexpectedly received a film commission, Die Goldene Gans (1944-7), which provided an income, but food and power shortages made living difficult.

In September 1948 she and Koch visited Alexander Kardan (with whom they had earlier collaborated on Prinzen Achmed), staying with him in London until November, when Reiniger had to return to Berlin. Reiniger left Germany permanently on 31 January 1949, re-joining Koch in London where they lived for some months at 236 Latimer Court, Hammersmith, W6, before moving in late 1949 to Wilton Cottage, Kings Road, Chalfont St Giles, Buckinghamshire (Happ, 2004, p. 67).

In London they received further commissions from the GPO Film Unit (renamed after the war the Crown Film Unit, part of the Central Office of Information), making many advertising films for them such as Post Early for Christmas (1950). Other promotional films included The Dancing Fleece (also known as Wool Ballet), for the English Department of Labor, and Grain Harvest (1950) for the Ministry of Agriculture.

In 1952 they established their own company Primrose Productions, with Viviana Milroy as producer and the financial backing of Louis Hagen Junior. Primrose Productions was primarily concerned with producing animated silhouette fairy tale films for children. Between 1953 and 1954 twelve such were produced and the 1950s would represent a highwater mark in Reiniger’s long career. These were made on a tricktisch that Hagen bought for Reiniger, and which was installed at the Abbey Art Centre, New Barnet, where Reiniger and Koch moved to in 1952.

Whitney Grace writes that ‘Reiniger and Koch were welcomed at the Abbey Arts Centre, finding that being around fellow artists helped inspire their own work’ (Grace, 2017, chapter 7). Reiniger later told Alfred Happ that the Abbey Art Center residents ‘… live in their separate households, but close enough to inspire one another. The museum provided me with a number of artworks from different parts of the world, it’s not only ideas, but a widening creative atmosphere’ (Reiniger cited in Happ, 2004, p. 82). When William Ohly, the founder of the Abbey, died in 1955, Reiniger painted a memorial window of St Francis of Assisi for the Abbey tithe barn, where it remains to this day.

Reiniger became a mentor to a younger Abbey resident, the English-born sculptor Peter King, whose experimental animated film, 13 Cantos of Hell (1955), was made using Reiniger’s shadow puppet techniques. Reiniger and Koch were also godparents to King’s first two children, Michael and Janet, born at the Abbey in 1953 and 1954 respectively. New Zealander Daryl Hill, who worked as assistant to Henry Moore during the mid-1950s alongside Lenton Parr and who was a probable visitor to the Abbey, became interested in film at this time through Reiniger and Koch, later citing their influence on his own experimental filmmaking in Australia in the 1960s (Laurie Thomas, ‘Those who are alone’ [interview with Daryl Hill], The Australian, 22 July 1967, p. 8). Given that Reiniger and Koch were two of the Abbey’s longest term residents—Koch lived there up until his death in 1963 while Reiniger remained until 1980—it is likely that other Abbey residents also came within their circle of influence.

After Koch’s death, Reiniger retired from film making but continued lecturing at film festivals and workshops in Europe and Canada during the 1970s. Her tricktisch lay disassembled in parts in her room at the Abbey until early 1980, when the director of the Düsseldorf Stadtmuseum, Hartmut W. Redottėe, wrote to Reiniger and asked to purchase it for the museum. After agreeing on a price, he flew to England to oversee the table’s packaging and removal from the Abbey and while there, observing Reiniger’s sadness, spontaneously invited her to come to Düsseldorf and make a film on the table at the museum as part of an exhibition he was organising for that September. The result, Düsselchen und die vier Jahreszeiten (Düsselchen and the Four Seasons), would be her final film. Reiniger left the Abbey permanently that year, moving to Germany where she lived her final year with the Happ family at Dettanhausen, Tübingen.

Sheridan Palmer

Bibliography

Lotte Reiniger, ‘Scissors Make Films’, Sight and Sound, vol. 5, no. 17, 1936, pp. 13–5.

William Moritz, ‘Lotte Reiniger’, Animation World Network, vol. 1, no. 3, 1 June 1996 (accessed June 2021).

Alfred Happ, Lotte Reiniger: 1899–1981 Schöpferin Einer Neuen Silhouettenkunst, Tübingen: Kulturamt, 2004.

Frances Guerin and Anke Mebold, ‘Lotte Reiniger’, in Women Film Pioneers Project, Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal, and Monica Dall’Asta (eds), New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2016 (accessed June 2021).

Whitney Grace, Lotte Reiniger: Pioneer of Film Animation, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2017.

Nicole Ackman, ‘Lotte Reiniger Was a Talented and Inventive Pioneer in Animation’, FF2 Media, 9 September 2020 (accessed June 2021).

David Sterritt, ‘The Animated Adventures of Lotte Reiniger’, in Quarterly Review of Film and Video, vol. 37, no. 4, 2020, pp. 398–401.

William Moritz, ‘Lotte Reiniger’, Animation World Network, vol. 1, no. 3, 1 June 1996 (accessed June 2021).

Alfred Happ, Lotte Reiniger: 1899–1981 Schöpferin Einer Neuen Silhouettenkunst, Tübingen: Kulturamt, 2004.

Frances Guerin and Anke Mebold, ‘Lotte Reiniger’, in Women Film Pioneers Project, Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal, and Monica Dall’Asta (eds), New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2016 (accessed June 2021).

Whitney Grace, Lotte Reiniger: Pioneer of Film Animation, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2017.

Nicole Ackman, ‘Lotte Reiniger Was a Talented and Inventive Pioneer in Animation’, FF2 Media, 9 September 2020 (accessed June 2021).

David Sterritt, ‘The Animated Adventures of Lotte Reiniger’, in Quarterly Review of Film and Video, vol. 37, no. 4, 2020, pp. 398–401.

Photograph (i)

Lotte Reiniger working at a table outdoors in the garden of the Abbey Art Centre, c. 1952-63, courtesy Lotte Reiniger Estate Collection, Stadtmuseum Tübingen, Germany

Date modified

15 January 2026

Collection

Citation

“Lotte Reiniger (1899–1982),” The Abbey Art Centre Digital Repository, accessed March 3, 2026, https://omeka.cloud.unimelb.edu.au/abbey-art-centre/items/show/911.