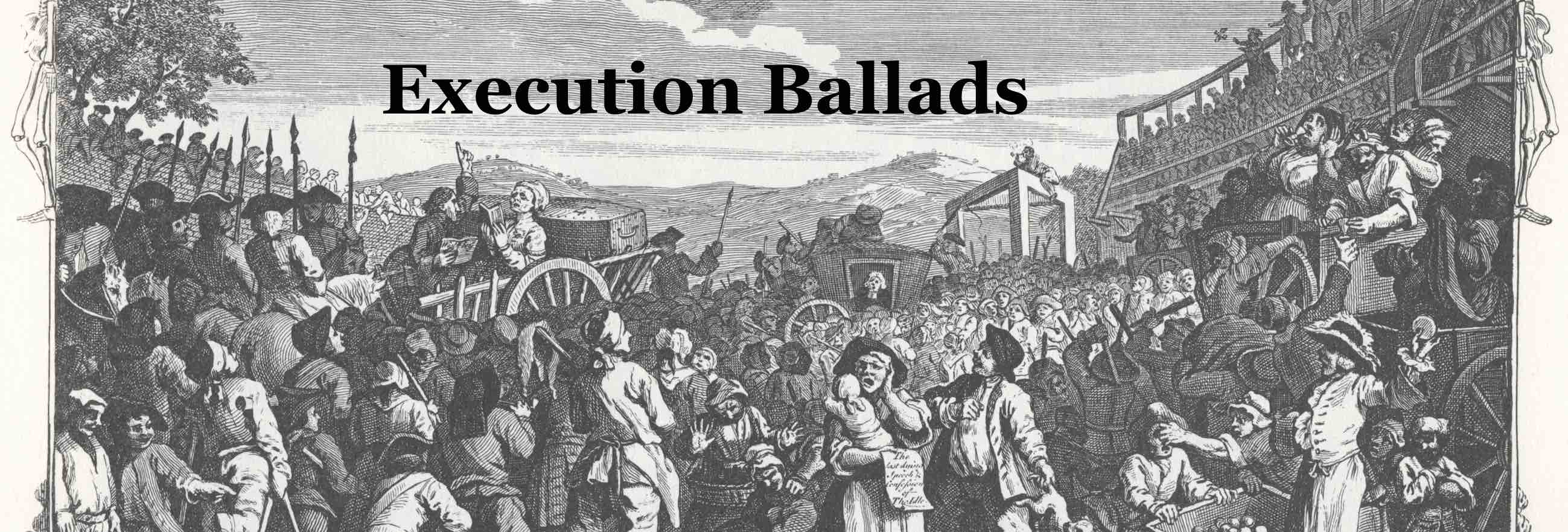

La Pendaison (The hanging), plate 11 from Les Misères et les malheurs de la guerre (The miseries and misfortunes of war) series.

Title

La Pendaison (The hanging), plate 11 from Les Misères et les malheurs de la guerre (The miseries and misfortunes of war) series.

Description

Callot has always been regarded as one of the exceptional artists of his time, although he never made any paintings; he worked exclusively as a printmaker and produced more than 1400 plates, almost all of which he designed and which earned him enduring fame across Europe. Callot hailed from Nancy, capital of the Duchy of Lorraine, were he grew up in elevated court circles and was apprenticed by his father to the court goldsmith. He departed for Rome at a young age, training there as a printmaker and forming his recognisable style. By 1614 he was living in Florence and working for the Grand Dukes of Tuscany, recording theatrical productions and court pageants. He returned to Nancy in 1621 and two years later was appointed artist to the Lorraine court under the patronage of Duke Henri II, but most of his activity involved commissions from religious orders and prints made independently for sale to the public. To this last category belongs Callot’s masterpiece, the series of 18 small etchings known in English as The miseries and misfortunes of war, arguably the best-known set of prints produced in France during the 17th century. The prints were marketed in Paris in 1633 by Callot’s friend, the publisher Israel Henriet, and the set was sold as a booklet, stitched together at the left side. Each plate (excluding the title page) contains a verse commentary in the bottom margin attributed to the voracious print collector, the abbé Michel de Marolles. Marolles famously sold his collection to Louis XIV in 1667, and it eventually became the foundation of the present-day print collection at the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris. Callot only made etchings but he handled the technique in a very particular way: he used a specially designed tool called an échoppe which allowed him to create elegant, swelling lines mimicking those produced by the engraver’s burin. Thus Callot was able to imitate the effects of the nobler art of engraving while sustaining the speed of execution peculiar to the process of etching. Working on a miniaturist’s scale, his animated vignettes are replete with detail; indeed, part of their fascination is due to the vast spaces and hopelessly innumerable crowds Callot managed to capture in such a reduced format. The miseries and misfortunes of war abounds with scenes of barbarity and carnage, and although it was not intended to be read as a sequence of documentary-like observations of real events, there is no denying the aspect of lived experience which runs through the plates. The socio- political context in which Callot made the prints was the Thirty Years’ War, a succession of conflicts that devastated central Europe between 1618 and 1648. What was initially a string of religious disputations between Protestants and Catholics erupted into a larger conflict between the Habsburgs of the Holy Roman Empire and the French kings, the Bourbons, for dominance in Europe. Lorraine sided with the Habsburgs; in 1633 the French army invaded Lorraine and in the following years the territory was ravaged by marauding troops, many of them mercenaries with no allegiance to their side, wreaking havoc on the lives of ordinary people and making violence part of the background of daily life. Callot’s series is less an indictment of war than a moral tale about the unhappy consequences that befall the undisciplined soldier. The descent into lawlessness is typified by the plate depicting troops looting a farmhouse and torturing the inhabitants. Other prints focus on the radical corrections administered by the military to corrupt soldiers: one such plate depicts the body of a criminal soldier being broken on a wheel, while in another, executed men hang from the boughs of a tree, the shocking spectacle belied by Callot’s refined touch and the measured elegance of the composition at large. The verse in the lower margin reads: : ‘Finally these infamous and abandoned thieves, hanging from this tree like wretched fruit, show that crime (horrible and black species) is itself the instrument of shame and vengeance, and that it is the fate of corrupt men to experience the justice of heaven sooner or later.’ Peter Raissis, Prints & drawings Europe 1500–1900, 2014

https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/explore/collection/work/41047/

https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/explore/collection/work/41047/

Creator

Jaques Callot (French, 1592 - 24 Mar 1635)

Date

1633

Rights

Public Domain: This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 100 years or less.

Original Format

Etching

Collection

Citation

Jaques Callot (French, 1592 - 24 Mar 1635), “La Pendaison (The hanging), plate 11 from Les Misères et les malheurs de la guerre (The miseries and misfortunes of war) series.,” Execution Ballads, accessed March 10, 2026, https://omeka.cloud.unimelb.edu.au/execution-ballads/items/show/1154.